Zahabi's Newsletter - Sept/Oct 24

Today we talk about writing in Manchester, how frustration can be a source of creativity, Dragonflight by Anne McCaffrey, and cloudy skies.

Dear reader,

A belated September newsletter, sneaking into October! Today we talk about writing in Manchester, how frustration can be a source of creativity, Dragonflight by Anne McCaffrey, and cloudy skies.

What’s happening with the book – Cast of Wonders & Manchester

I have a short story out! I’m particularly pleased that this one is being published, as I wrote it ages ago and struggled to find a home for it. It finally found its place with the online podcast Cast of Wonders. According to Word, the first draft of this was written in 2020 – so, four years later, here it is at long last. I wrote Three Wishes to Save the World while still living in Manchester, and the story is set there, so I really appreciate Cast of Wonders picking a narrator with a Northern accent to read it.

Talking about Manchester, a friend spotted my first book, The Game Weavers, on the shelves of Queer Lit. It’s a lovely indie bookshop in North Manchester, and I can’t tell you how nice it is to have friends send pictures of books they’ve stumbled upon in bookshops. Especially as The Game Weavers was published by the indie press Zuntold and has never had much publicity around it, it warms my heart every time I spot it.

What’s happening on the page – On Creativity & Frustration

I was talking with a colleague at work about how it’s impossible to recommend books to yourself, yet the best person to recommend a book you’d love is yourself. I was imagining what it’d be like to have my reading list dictated by a Rebecca who had already read everything she could read in a lifetime – she could recommend only the good books. Skip all the dross, go straight to the stuff that makes my heart sing. My colleague then pointed out that, if I didn’t ever read books I disliked, I might never have the impetus to write myself – and everything I write would feel mediocre in comparison.

This echoed with something I’ve read recently about fanfiction. I can’t remember where, exactly, but someone was defining fanfiction as the result of both love and frustration. Love, in order to engage with the work. Frustration, in order to change it. The reasoning was that, if the work is too perfect, why bother writing a fanfic? They argued that the act of writing comes from wanting to scratch an itch, rewrite the parts that don’t feel quite right, insert something that’s missing.

And I think that’s true. A great impetus to write is frustration at not seeing the story we want told out there in the world. The first book I ever wrote, I wrote because I was frustrated. I read a children’s book which contained a school for knights, for boys only; and a school for wizards, also for boys only. One school for boys only I might have tolerated, even though, being a knight at heart, I was disappointed I couldn’t be one. But two schools for boys? This was a step too far. I had to correct this grave injustice, by writing a story where a boy goes to an all-female school for witches, and a girl goes to an all-male school for knights.

It's interesting, because if a book is just too bad – we don’t engage with it at all – then we don’t even want to bother rewriting it. And if it’s too good – just too skillful – we love it as it is, without wanting to change it. (This is how I feel about most Ursula Le Guin I read.) But there is great creative energy to be found in books that frustrate us.

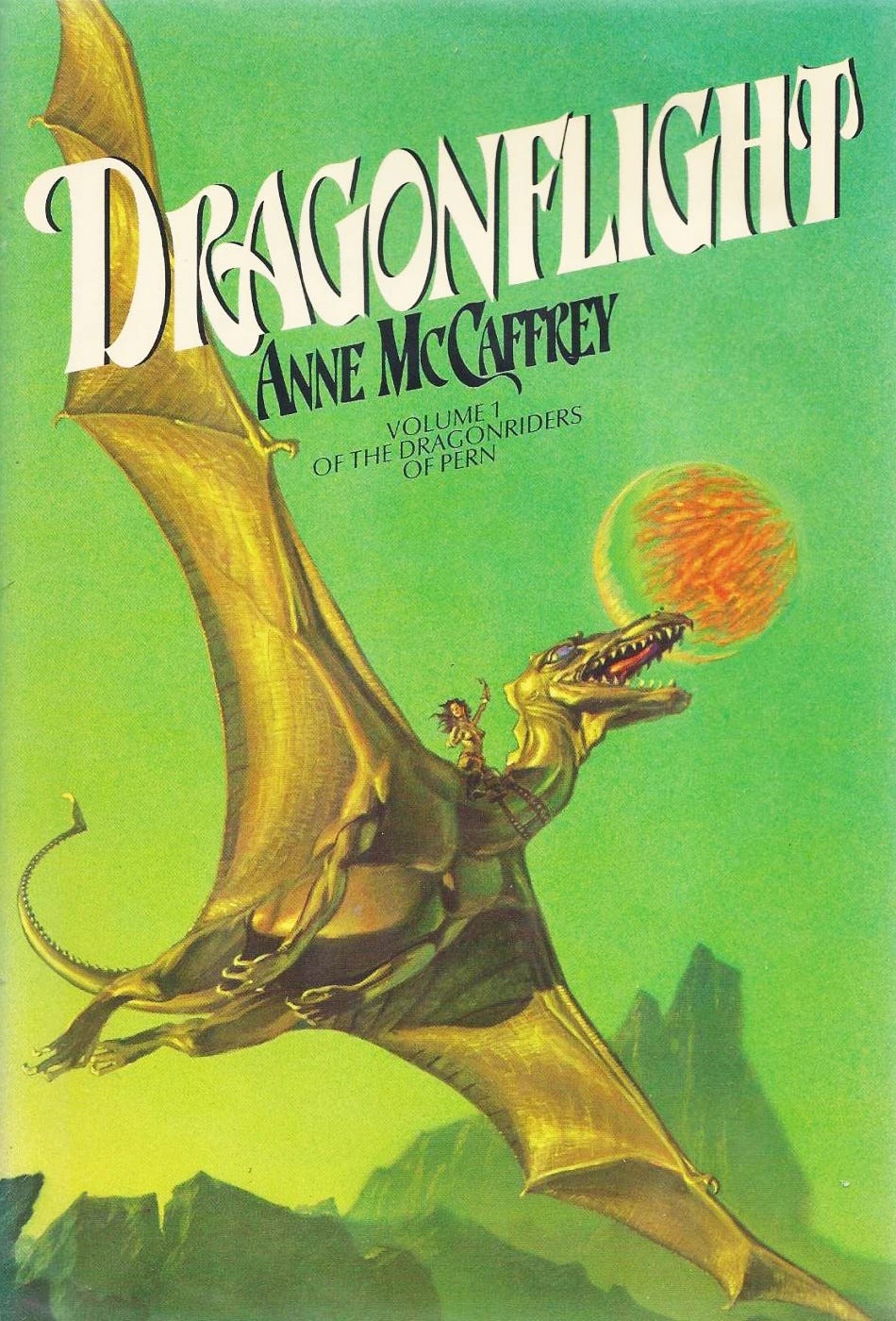

This brings me to Dragonflight by Anne McCaffrey. I read it because it’s a classic, written by a woman, and I’ve been trying to read SFF from the 70/80/90s written by women that I might have missed. In part, this is how I stumbled upon writers like Nicola Griffith, Lois McMaster Bujold, or Patricia McKillip.

Now, I’d like to put a disclaimer upfront: I have only read Dragonflight, with no knowledge about the series, Dragonriders of Pern, as a whole. My understanding is limited to that one book. And I want to be brutally honest: I hated it.

Or rather, I felt deeply frustrated by it. Who doesn’t want to fly on a dragon? Who doesn’t want a female lead? From those elements alone, I can understand why it was successful in its time. But, for starters, it is incredibly sexist. (I’d like to point out that being published in 1968 doesn’t feel like a good excuse for sexism, not when The Left Hand of Darkness was just around the bend in 1969.)

Our main character is told female dragonriders can’t fly their queen dragons, and then gets to fly her dragon. Okay, great start! But also, she is raped by the love interest – who remains her love interest. No-one takes any issue with the rape. The love interest is also physically abusive – he “shakes” her at several points in the novel, and when she disobeys him, she says pitifully: “Oh no, he’s going to shake me!” From the descriptions, I take it that he grabs her by the forearms, that he’s bigger and bulkier than her, and that he violently shakes her to shut her up. Suffice to say, I’m not on board with this.

But I can see what McCaffrey was trying to do, and I felt the urge to do the same – write a society in which a young woman is thrown; she realises it’s deeply patriarchal but that she has a unique place in it, being their current dragon queen person; and she uses that role to enforce change. Our main character can talk telepathically to all the dragons. I was immediately interested in a conflict arising between dragons and (male) dragonriders. What if the new queen is allying with the dragons behind their riders’ back? What does that look like? If someone you can share thoughts with is in distress, surely that affects you? Anything that sits badly with our main character would, in time, sit badly with the dragons themselves.

Another element that frustrated me was the wyrm, officially called a watch-wher. Probably no-one remembers the watch-wher: it is a small ugly dragon (or maybe a really big lizard, I’m fuzzy on what it actually looks like). It’s a creature that’s often described as pathetic, living with our main character before she joins the dragonriders. And when she joins them, they tell her to ditch the wyrm. It’s not a proper dragon. It can’t fly. It’s not high-born. If dragons are wolves, this wyrm is a pug.

After being told she has to abandon it, it’s conveniently killed to avoid dealing with the narrative consequence of its existence. The dragons do begrudgingly acknowledge the wyrm’s bravery, but they don’t have to live in their cognitive dissonance for long, thanks to the deus ex death. They never question their prejudice for other little wyrms.

Reading this, I was fuming. My wyrm is not a standard dragon. Sure, so what? It’s loyal and brave and also my friend, whether it’s useful or not. If it were my loyal ugly dragon-like animal, I’d be damned if I didn’t bring it with me! I could see that scene. I was writing it in my head even as I was reading McCaffrey’s work. I knew the cool one-liner I’d have, how I’d throw myself in front of my wyrm, how a bigger dragon would have to intercede, how power and prejudice and righteousness would get a chance to be expressed in the scene. How dragons are worth more than their usefulness. That that’s not the way we should look at sentient beings – or any creatures, really.

There is something deeply classist, nearly eugenic, in parts of Dragonflight. Notably the idea that good qualities are innate to high birth, that low-borns are ugly and lesser in some intrinsic, unsurmountable ways. There is the notion that any form of disability, be it by birth (you were born a wyrm) or by misfortune (you’re a dragonrider whose dragon has died) makes you unfit to live with the dragonriders. But as I was reading, I could see solutions. Some of them were easy solutions – surely we can work out a place to live where not being able to fly doesn’t mean you have to be kicked out of the community? Let’s invest in pulleys and rope! Some of them were harder – surely my little wyrm (that I’ve brought with me to the dragonriders’ lair) will protect me from attempted rape?

I itched to write my own version of Pern.

So, what’s the result? I read a book I had issues with. I read a book that frustrated me, that I wanted to hate – yet that, on some level, also inspired me. I didn’t only want to discard it. I wanted to write my version of it. I could see space in this novel where I could do something with it, something that felt better to me. I felt the urge to answer.

I don’t know if I’ll ever write Wyrmflight. But I think there’s something interesting to mine here, some connection between works that frustrate us and works that inspire us. There is creative richness to reading books we dislike, or have issues with – especially books from the literary canon, that have enshrined certain ideas or concepts into the genres we love. Frustration urges us to put pen to paper.

What’s happening with me – Change of Seasons

This month, I travelled back to France to see some family. I noticed once again that when you travel, you travel through seasons. It’s late summer in Provence, long after the figs have rotted and the grapes have been harvested; it’s just about time to collect grapes near Lyon, and the figs are bursting on the trees; the leaves are already red back in Guildford.

I hiked for a year with my partner during my sabbatical. We travelled south during the winter, chasing the sun, and autumn kept happening to us, wherever we went it was on the cusp of winter, until it finally caught up with us. The return journey happened during spring, heading north: everywhere we went, trees were blossoming for the very first time. Walking in step with a season feels special, as if you’re catching up to time.

It now feels like we’re fully in autumn – the weather has turned, the holidays are over. The sky in Guildford is beautiful, with twisting clouds and wonderful colours, long sunsets that stretch out across the horizons.