Zahabi's Newsletter Nov/Dec 24

Plot armour, Some Desperate Glory by Emily Tesh, videogames, and end-of-year musings.

Dear reader,

In this end-of-year newsletter, I was hoping to look back on the year 2024, on where the writing’s at and where to go next. I’ll also spend some time talking about plot armour in stories, with some light spoilers for Some Desperate Glory by Emily Tesh. I’ll end with some highlights of videogames I’ve played this year.

What’s happening with the book – 2024 Haul

This year marks the end of the trilogy, with The Lightborn coming out in hardback. It’s been a long road, for a story I started writing 6 years ago. It was worth the effort. I’m proud of the story and where it lands, and I think I’ve managed to say what I wanted to say. It’s been a rocky road, from first draft to the Hachette Future Bookshelf competition, to finding an agent and a publisher and experiencing being traditionally published for the first time. I’m glad I can finally see all three volumes together on the shelf.

It's also been a good year for short stories: I’ve always struggled to find a home for my short fiction, and I don’t write lots of it, but when I do, I usually find it’s a tighter, more succinct version of the thoughts and themes explored in my novels.

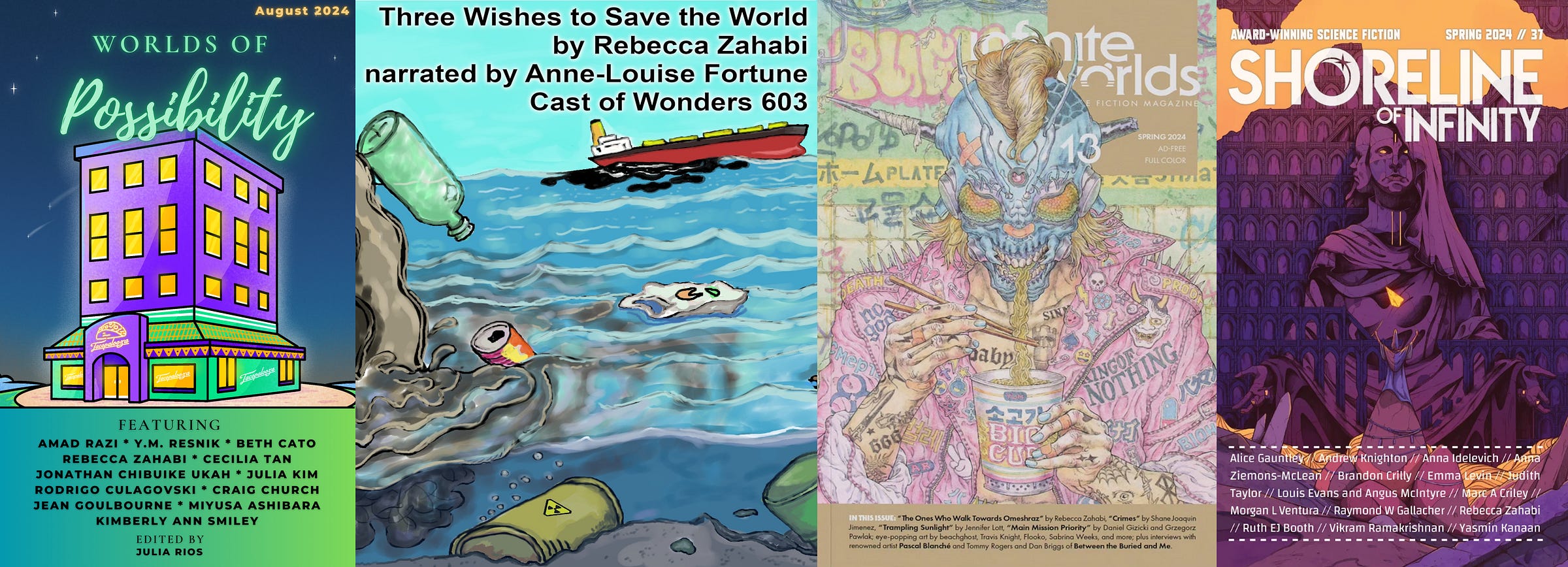

The 2024 cohort of short stories are:

· The Commute of the Valkyries in Shoreline of Infinity

· The Ones Who Walk Towards Omeshraz in Infinite Worlds

· Shooting Stars in Worlds of Possibility

· Three Wishes to Save the World in Cast of Wonders

Next year will be more uncertain. The next manuscript is out on submission, and I don’t know yet where it’ll go and what will happen to it. I’m worried about quite a lot of things, both concerning publishing and writing, such as generative AI; and concerning the world at large, such as polarising politics, the rise of the ultra-right, and the violence we’ve seen enacted across the world. I always felt I wanted to be a writer in order to change the world, but I’m not always sure I’ll be able to – sometimes I wonder if fiction is strong enough for what lies ahead.

I’ll try hard to stay hopeful and look towards the future. And I hope you get to do the same: keep scribbling, keep thinking up better worlds, keep dreaming of the change we can bring through our stories.

What’s happening on the page – Plot Armour

What is plot armour? When talking about stories, plot armour is generally used pejoratively, to indicate a character who should have died, but survived for narrative convenience. In short, the story spared them because it still needed them.

“Should have died” is interesting to unpack. All stories require suspension of incredulity. Everyday rules don’t apply. We never say of a character that they have plot armour because they didn’t randomly get run over by a car or die of a heart attack. Plot armour, in a lot of cases, is about the reader’s expectations.

For example, in comedies, we don’t expect to see main characters die. We never say of a Terry Pratchett book that the characters have plot armour – it’s supposed to be funny, and it wouldn’t if characters we cared about died, so they don’t. Our expectations as readers are met. In any Octavia Butler book, readers have to be braced for death, rape, and other forms of physical violence. It doesn’t make for a comfortable read. Butler isn’t interested in comfort. If halfway through the Parable of the Talents, characters we liked conveniently stopped dying, it would be a very different book. If anything, Butler does the opposite: she kills characters we’d expect to survive, to remind us that violence isn’t picky about its victims.

The problem with plot armour is, fundamentally, a problem about stakes. If readers expect something, (for example, we are told a fight is dangerous), but that threat is never executed, then we get that negative “plot armour” reaction. What we thought was a threat is a false threat. It’ll never happen. Therefore stakes shouldn’t be built around it, and if they are, it feels fake.

In the example above, if we know the main character is never going to die in a fight, we have to be given a better reason to care about the fight than “but they might die!” And there’s plenty of reasons to care: the stakes of the fight don’t need to be life-or-death situations. Whoever wins or loses a particular battle could gain or lose something, or move the plot in a particular direction. That’s where the tension will come from, from the threat of an outcome we want to avoid.

I got halfway through Some Desperate Glory by Emily Tesh, and then was struck with a bad case of plot armour. The themes set up at the start of the book are serious – we’re in a dystopia, with a radicalised main character who is blind to her own failings, in a militaristic society. We fully expect someone to die at some point. When we get to the mid-act point, without spoiling too much, a couple of main characters die and a huge, horrible, world-defining event happens. So far, I was sold.

Then a machine is used to skip into a parallel universe where all of this didn’t happen. And then the same machine is used again to go back in time and do it all again, only do it right this time.

The problem for me wasn’t necessarily the time-skip and the parallel universes (although these are always a hard sell for me) but the sense of stakes. After that mid-act point, nothing in the book worried me. I felt no tension. I wasn’t worried during the final battle and found myself skimming through it. I knew everyone would be fine. I’d been told to care, that people could die, that radicalisation has consequences – and then I’d been shown it hadn’t. By undoing death, for me, Tesh had undone the stakes. Time-loops are a form of plot armour, as are parallel universes – that’s why they’re hard to pull off. Why care for what’s happening here and now, when we could just undo it all with a click of our fingers?

Obviously, this is a hard balance to strike. If a writer kills off all of the main cast, the stakes drop because we’ve got no-one left to care about. If a writer threatens to kill characters and then doesn’t, the stakes drop because readers no longer believe in the threat.

I believe there are some tricks writers can use, to keep the stakes high and the readers invested, while not going on a murder spree. Here are a few ideas to explore:

Firstly, plan to kill one important character early on, at a point in the story in which it feels unexpected. Nip a blooming character in the bud. They still had so much potential – and that’s exactly why you murder them. It’s a way to show readers you’re serious. (This is very much what Full Metal Alchemist does. Be careful about overusing this, however – comedic characters who die before things get serious is a trope, as are mentors dying, so neither of those will have as much impact, because they won’t feel unexpected.)

Secondly, maim characters instead of killing them – both physically and mentally. If characters pay a price for their defeat, if they lose something or are damaged in some way, then readers know fights are serious. You can keep people alive and yet take something from them. This is something I did a lot in The Lightborn. It was a question I asked myself: who to kill, who to let live, who could carry the final beats of the story. And who could I maybe harm, in ways that meant they could still carry their plotline forward, while giving the reader a sense of the stakes and danger.

Alternatively, you could have characters MIA because of wounds, but continue the story in a way that ensures their absence is felt. The process of recovery is made a lot more real if the absence of a character in a scene has negative consequences, and makes us miss them. We’ll then be waiting impatiently, as readers, for them to be able to get back into the story. (This links back to the idea of a losing battle having a narrative cost of some sort.)

Thirdly, you could show the villain enact violence on a minor character (and go through with it) as foreshadowing. This is another way to show readers you’re serious. When your villain enacts a similar violent act against the main character, in a high-stakes situation, readers know they’re capable of going through with it. They’ve seen it happen before. They know you, as a writer, have done this and are not afraid of it. Sometimes, plot armour is simply a question of believability – and as such, some sleight of hand can be used to make sure readers believe your threats.

These are just some thoughts that I had around plot armour, and ways to avoid a character surviving feeling constrained. Sometimes, though, it’s worth just going for the killing shot. I’d have loved a version of Some Desperate Glory where, at the midway point, all the wrong decisions have been made, everyone important is dead, and it looks like nothing can be salvaged. I’d love to see a main character recover from that.

It makes for a more difficult story to read (and to write), but it can make for a better one.

What’s happening with me – Game Recommendations

I started working for Larian Studios in March. I realised I’ve learnt a lot over the course of not-quite-a-year, and I’ve played a lot of games (with narrative elements, mostly, but not only) and that I’m starting to have a mental library of games that rivals my mental library of books. So I thought I’d share some of the highlights!

Tactical Breach Wizard is very good, and reminds me of The Banner Saga somewhat, in the way it balances story and gameplay. It’s got a lovely story, witty dialogue, some fun tactical combat that feels like a puzzle with plenty of ways to solve it. The characters are believable and warm, the story touching, the end holds up to scrutiny. I’d warmly recommend it.

Chants of Sennaar is a great puzzle language game. It has an interesting vibe and setting. I particularly loved walking around with half-translated words and trying to work out what people were saying to me. Lots of environmental storytelling is happening, with the gorgeous art telling us as much about the world as the words themselves. I’m not so sure about the end, but it’s still one of the best games I’ve played this year.

Slay the Princess had some interesting ideas and narrative loops. The art is great. The concepts behind the story, and the way it’s structured, are fascinating to explore. I found the tone of the narrator sometimes clashed with the artwork and music (the narrator felt too funny and irreverent for the horror that the art was clearly going for), but aside from that, it’s very successful.

Cultist Simulator and Book of Hours were interesting to me in comparison. I love the particular shade of creepiness The Weather Factory are going for. With Book of Hours, I was expecting an easier Cultist Simulator (which it is) but, funnily enough, although I thought that’s what I wanted, my conclusion is that Cultist Simulator is the better game. Cultist Simulator is harder to access, and it can be frustrating, but I do believe – even more strongly now – that it’s a masterpiece. The way the gameplay is used as an intrinsic narrative tool is just so clever. In both games, the story is well worth diving into, and the world-building is delivered entirely through titbits, leaving the player to put the pieces together.

That’s it from me for this year! See you all again in 2025.