Zahabi's Newsletter - May/June 25

Witches in contemporary French fantasy, author resilience, bluebells

Dear reader,

This month we talk about witches and women, fairy tale magic, bluebells, AI scraping, and author resilience – we’ve got plenty of subjects to explore! Let’s dive straight in.

What’s happening with the books – Author Resilience

As part of my ongoing battle against generative AI, my latest discovery has been how much AI bots trawl my personal website. I hadn’t realised this, but Wix has analytics for this. For example, 1,503 bots went through my website the past month (far more than humans) and scraped the articles written there to feed their “AI summary” page or answer people’s questions. (Mostly, for some reason, they steal from the Romantic Tension article.) I don’t have these stats for Substack, but I imagine it’s similar.

If any of you out there have a personal website, this may be something you’d want to check! Some people use digital “tar pits” to trap bots on their websites and feed them nonsense, although I have to admit I haven’t bothered yet – preventing AI from scraping my books is the priority, as far as I’m concerned. Or you can simply go the LitHub route, and just write a nonsense article to feed the bots.

My next manuscript is out on submission, but the whole process is so slow, it feels like life has become a long wait peppered with rejection emails. This is all part of the process, and the reason why resilience is such a big part of being an author, but knowing that doesn’t make things easier. To any fellow authors out there waiting on some good news – I feel for you! Interestingly, the Society of Authors put out an Author Care Toolkit, and there’s some useful tips there for authors feeling at loose ends. At the very least, it’s good to know we’re all in the same boat.

What’s happening on the page – On Witches

Recently, I decided to read more SFF books in French, as I’ve been out of the loop as to what’s being published in France at the moment. I found myself picking up two books, both published in 2023, both urban fantasy, with witches at their core. I realised, belatedly, that witch lit is a subgenre in itself – I knew I was out of the loop! – and found it interesting to explore the similarities and differences between both books.

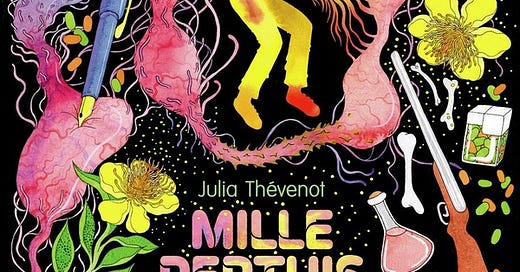

So today we’ll be comparing Mille Pertuis by Julia Thévenot and Du thé pour les fantômes by Chris Vuklisevic. What did witch lit allow for? Who did it empower? What sort of stories did that subgenre encourage?

A few things I noticed straight off the bat: both books had a big cast of women. They also had a matrilineal story – lots of mothers and sisters were involved. The stories focused on mother issues, sibling rivalries, ambitious women walking in their mother’s footsteps. We see so many fathers in stories, while mums tend to die offstage in the early chapters. But if the power is matrilineal, suddenly the story has to be, as well. Du thé pour les fantômes is nearly entirely focused on the relationship between two sisters, how their mother drove them apart, and how their grandmother set up the rest of the family’s troubles. This means women are not just the one secondary character or romantic subplot. Instead, they – and their family ties – are central to the story.

It may seem obvious that witches imply women, but it’s interesting to me that gender is such a big part of what witches represent. Witches crystallise something important – women being murdered and burnt to death, mostly for daring to be knowledgeable, independent, or non-conformist. Historically, witches come much later in the Middle Ages than people assume. It’s more around the Renaissance than the so-called “Dark Ages” that they’re persecuted, roughly between 1500-1700. Basically, while people are experiencing a renaissance in art, culture and science, there is a correlated backlash against these new ideas, mostly hitting women. (Although some men were burnt as witches too.)

So witches act as a symbol of conservative pushback against controversial ideas, and as powerful women who scared men enough for them to create a whole inquisition to destroy them. This particular historical background means “witch lit” tends to be about being non-conforming in some ways, outside of society, and it allows for stories that explore that particular space.

It also allows for powerful women. Witches tend to be a lot more powerful than standard female characters, who may have strengths and weaknesses, but generally have to deal with a patriarchal setting (with some exceptions, of course). Witches, interestingly, aren’t set in a particularly feminist world – or at least, not the two books I read. But they could fight back in ways most women can’t.

For example, in Mille Pertuis, our heroine hitchhikes at night when she’s only a child. This would usually be pretty terrifying because of the risk involved – as a reader, I’d be worrying about everything that might go wrong, thinking of a child alone on the road waiting for a stranger to take her into their car. But she’s got magic powers of persuasion which make her able to manipulate people, and in this world most witches are women. The only people who could resist her powers are unlikely to hurt her. This removed the ever-present risk of sexual assault or harassment. To me, this was a liberating moment. Having a female character who can simply not worry about sexual assault, who can be safe from it without needing to account for its possibility, is deeply satisfying. Mille Pertuis still addresses, later in the story, how vulnerable this character would be without her powers. But, briefly, gloriously, we can enjoy the adventurous side of a kid hitchhiking at night without fear.

Another common ground between both books was the magic system. In both cases, it was very close to magical realism: although the stories were set in 21th century France, the powers were odd and often visceral, involving blood, nail cuttings, tea, taste, etc. They often followed fairy tale rules, as most “soft” magic systems do. Write someone’s name on a piece of paper and dip it in milk. Then, if you eat it, you will taste that person’s character. Or be saddled with a curse that means an insect crawls out of your mouth for each word you speak – and walk around with a vacuum-cleaner close to your lips when you’re trying to have a long conversation.

In both worlds, witchcraft was reserved to women, although Du thé pour les fantôme did have a male shepherd with his own brand of weather magic, linked to the local Nice folklore, called a tempestaire. Mille Pertuis also raised questions of gender identity: what if you’re born a male witch? The second POV character in the book is a young man who desperately wants to be accepted into Hogwarts, and finds himself saddled into a very different magic system. He’s an oddball, he has no-one to teach him, he’s not recognised by the witches as one of their own. He’s not very happy to be forced to deal with a soft magic system, of weird ingredients and rituals, when what he really wanted was a nice list of spells and a mathematical approach to the occult. This raises an interesting conversation about how soft/hard magic systems are perceived, and sometimes gendered.

(If you’re interested in the gender divide across soft/hard magic systems, I’ve got a whole article on that topic already, so I won’t delve into it too much here.)

In summary, witches are an interesting choice through which to explore women’s stories, gender, fairy tale magic, and rephrase them in a modern setting. I’m curious to see what other witchy books might be on the horizon, and what they might be adding to the conversation.

What’s happening with me – Bluebell Hikes

Spring means it’s time to hike and enjoy the bluebells which briefly grace the woodlands. I’ve been enjoying the warmer weather, taking the dog on long walks, and fighting a losing battle against the slugs and snails to protect the few flowers I planted.

I’ve also been reading The Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Ghanzhong. For the time being, there isn’t much romance, although there is plenty of civil war. I always love reading very old stories, coming from an oral tradition, because they tend to have a deliciously matter-of-fact approach to magic. The book presents mostly as an oral history. It’s giving us facts: this battle happened. This person lost. And then, sometimes, it gives us facts we might question: this person summoned clouds. This person made a dragon’s liver appear in their sleeves. This person couldn’t be burnt to death because they were immortal. The supernatural and the historical weave seamlessly together, giving us a world where magic isn’t just possible – it’s commonly acknowledged as fact.

That’s my preferred way to enjoy the sun at the moment: by lying outdoors to read about Chinese civil wars. I would highly recommend!