Zahabi's Newsletter - Jan. 24

Cancel Culture in The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin, The Hawkling out in paperback next month, and snow.

Happy New Year everyone! 2024 is under the sign of change.

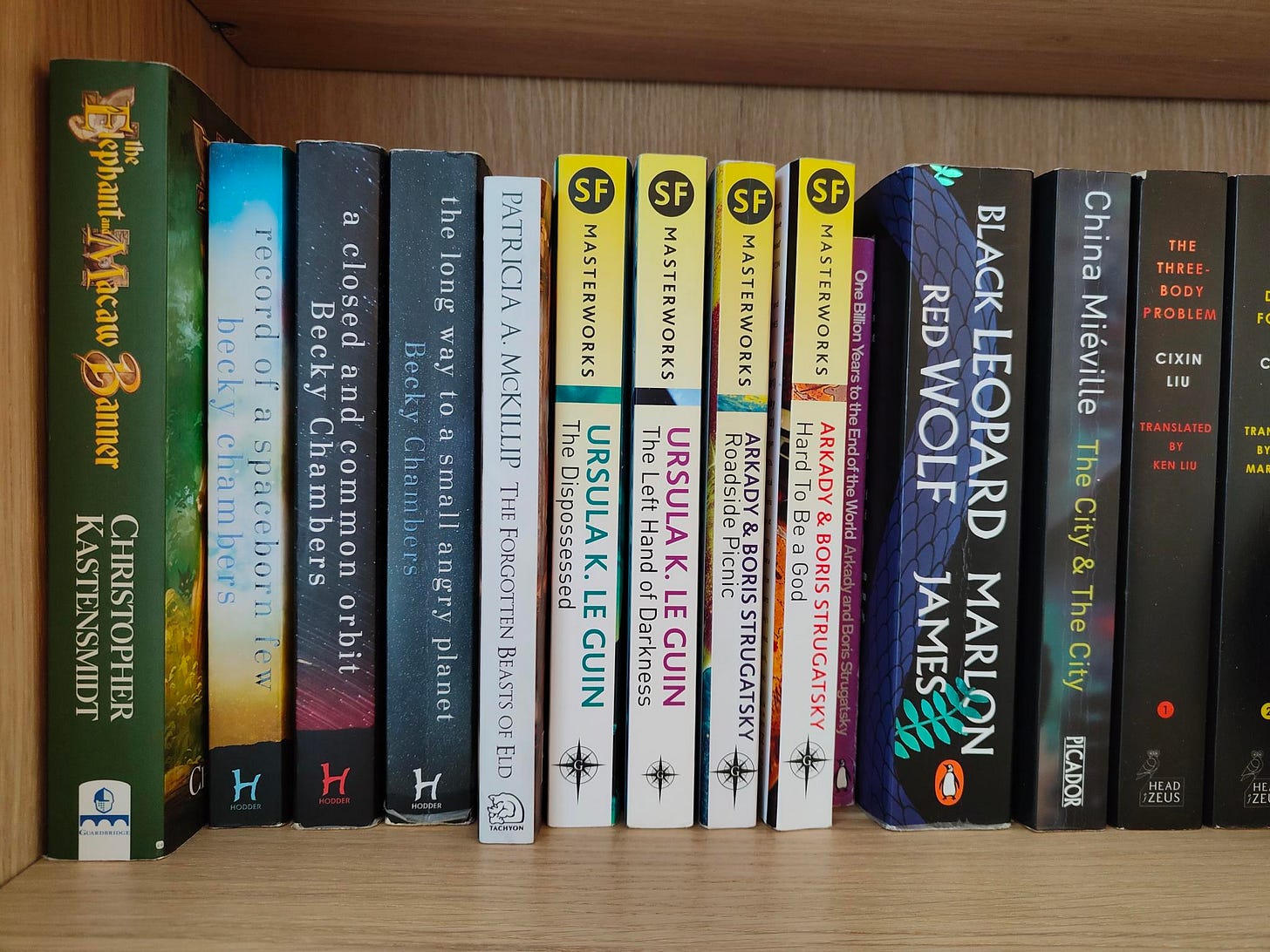

This month, the newsletter is moving to Substack, after three years (three! I still can’t quite believe it). I started these articles with Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, so it seems appropriate to start this new year with Le Guin again. The article this month is about cancel culture – a thorny topic – and how it’s treated in The Dispossessed.

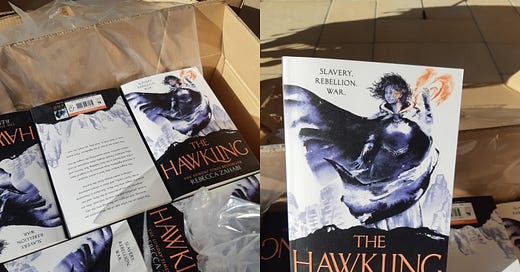

In other news, the start of 2024 is going to be a busy time for me: The Hawkling is coming out in paperback in February, The Commute of the Valkyries is being published in Shorelines of Infinity in March, and The Lightborn is out in May. Busy times!

What’s happening with the book – The Hawkling is out in paperback next month!

The Hawkling is out in paperback next month! After many shenanigans (my paperback copies got sent to my parents’ address in France, at a time when my dad was travelling and my mum was at work, so we managed to miss all three delivery attempts and then had to beg UPS to actually give us the books and not send them back to the UK), I received The Hawkling paperbacks. Hurray! You can also get them (hopefully with less drama) by ordering them in your local library or the Gollancz website – if you pre-order them now, you’ll get them on the 1st February.

I have a preference for paperbacks over hardbacks, maybe because that’s what I’ve most often bought or borrowed from libraries, so it’s always a pleasure for me to get the paperbacks. We commented on the difference between French and UK paperbacks with my mum (the French ones are smaller, and are called ‘poche’, which means ‘pocket’. Traditionally, they’re meant to fit into a coat pocket.) And we had fun ‘unboxing’ them together over WhatsApp.

What’s happening on the page – Cancel Culture in The Dispossessed

With minor spoilers for The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin

Introduction

In The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia by Ursula K. LeGuin, there is a playwright called Tirin, who writes a play that is considered immoral. What happens to him is described in these terms: ‘Tirin wrote a play and put it on, the year after you left. It was funny – crazy – you know his kind of thing. […] It could seem anti-Odonian, if you were stupid. A lot of people were stupid. There was a fuss. He got reprimanded. Public reprimand.’ After the play comes out, a lot of people disapprove of it and consider it morally disturbing. Tirin gets publicly shamed and is encouraged to work in anything but playwriting. He does, for a couple of years, and finally ends up in an asylum. He’s described, by people who see him after he’s got out of the asylum, as a broken man: ‘a destroyed man.’

Does this process sound familiar? It seems to me that Tirin was cancelled – this happens, similarly to cancel culture today, through disapprobation of a large part of the audience. The audience then ignores and isolates the playwright, Tirin, and publicly shames him, until he finally gives up on writing. The planet Anarres in The Dispossessed is a utopia, yet Ursula Le Guin’s main character, Shevek, disapproves of the cancellation and sympathises with the playwright.

What can we learn of LeGuin’s treatment of controversial art in her fiction?

Definitions

Cancel culture has been used as a bracket term to mean a lot of things. So, before we go any further, let’s make sure we agree on the definitions. Cancel culture generally expresses either disapprobation of the work (the art itself is immoral), or of the artist’s lifestyle (the artist is immoral), or the artist’s opinion which they’ve expressed publicly (the artist’s beliefs are immoral). The action of cancelling can be defined as a form of boycott: a group of people refuse to engage with the art. Often, the cancellation goes one step further: it’s about vocally expressing disapprobation, encouraging others to boycott the art, and sometimes asking for the art to be removed entirely and made unavailable.

I’d like to point out that boycotting a piece of work is, historically, a way for consumers or the public to fight back against privileged groups, in an environment where it’s otherwise impossible to exert control. Refusing to read someone’s work, as an individual, may happen because the person feels they’re not going to get justice any other way. As a vegetarian, for example, I refuse to buy meat and engage with the meat industry at large, hoping that, if enough people do so, we’ll force the meat industry to either change their practices to make themselves acceptable to us – by introducing better animal welfare practices – or that they’ll disappear altogether, because they don’t have a market.

In a capitalist society, what makes money is a form of market control over what gets written, read and published. Because of this, refusing to buy something is a way for the readers to exert power over the publishing industry, when normally they have very little say.

I draw a line, however, between that form of boycott and insulting, persecuting, and sending death threats to the artist. That’s harassment. Harassment has been a part of cancel culture, but to me, boycotting a piece of work because you think that’s the only form of justice you’ll get, versus actively harassing someone, are two different behaviours. Boycott is activism. Harassment is a crime.

(I will not go into extreme cases, such as state censorship, physically assaulting authors or calling for people to physically harm them – for the purpose of this article, let’s exclude those from our definition of cancel culture.)

Cancel culture, at its worse, is harassment. But what it’s trying to do, I think, is to ostracise and/or shame the artist. The idea of being ‘cancelled’ implies forbidding a piece of work, or all work from the artist, because either the author and/or their work is disapproved of. The readers then try to ‘cancel’ either the work or the author, by discouraging others from reading the work, or discouraging the author from producing more work. This may include limiting places where the author can speak/publish/express themselves. At its core, cancel culture is a moral judgement, followed by a punishment.

(I’m a law and philosophy graduate, so these terms aren’t maybe as loaded to me as they might to be to others: moral judgements are necessary to live within a society. Without judging what’s right or wrong, we don’t get to choose a society that is good. Of course, the fighting starts when deciding what is actually good or bad.)

Ostracism is a relatively mild form of punishment, and is used in societies as a way to dissuade criminal behaviour. Ostracism means isolation: ‘now we all ignore you and no-one engages with you, until you realise you’ve said things that have upset us and shut up.’ But ostracising someone is a form of punishment, and in that sense it always has a violent component to it. (We’ll get back to this with regards to Tirin.)

So, we’ve got some working definitions, and we can see why readers would want to cancel/boycott books, or ostracise authors. The important question is, should we, as readers, be cancelling authors?

The Cost: What we lose

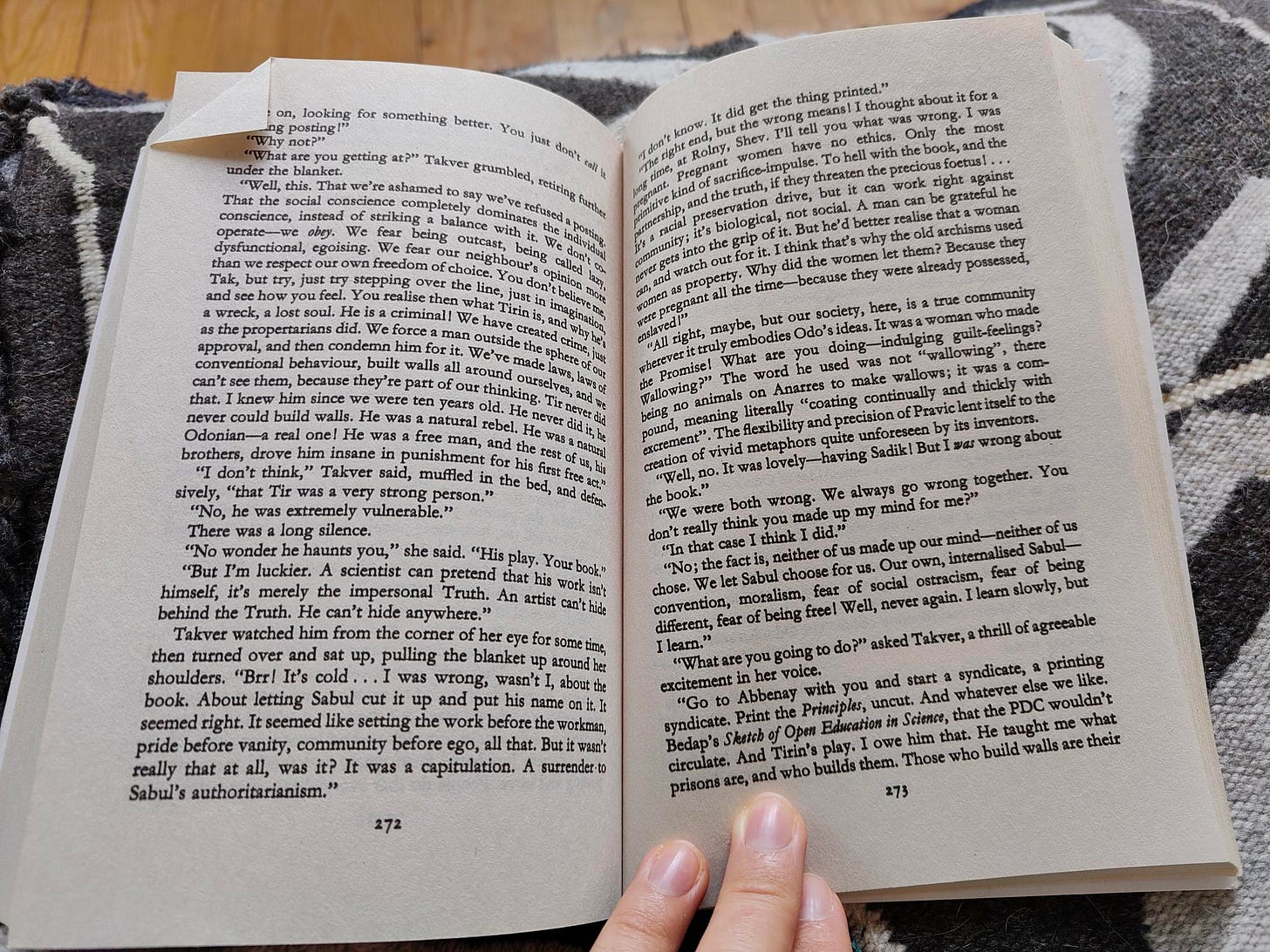

In The Dispossessed, Shevek is upset when hearing about Tirin’s fate: ‘He was a free man, and the rest of us, his brothers, drove him insane in punishment for his first free act.’

Tirin isn’t a criminal, but his writing is disapproved of. We know that whether or not the play is immoral is controversial – several characters say it’s funny, imperfect, silly, maybe a bit shocking, but they don’t seem to think anyone could’ve been scarred by watching it. This is very common in cancel culture today: people rarely all agree on whether the work is problematic, or which bits of it are.

Tirin’s punishment drives him mad, because in a highly collaborative society, ostracism is extremely harsh. He is also publicly reprimanded – so publicly criticised for his play. The public element of the reprimand is meant to shame him, not unlike people are shamed online when audiences try to cancel them. Shame isn’t about dialogue or understanding; it is, at its core, a punishment. I’m not saying that public shaming and ostracism might not be useful tools. But we have to acknowledge that, when using them, we’re harming the person we’re aiming them at. They’re coercive tools to control behaviour.

At a guess, people who have been targets of cancel culture have worse mental health afterwards. Like Tirin, we are all vulnerable to group shaming. Artists are normally in a place of self-reflection and self-criticism anyway, so we’re particularly vulnerable. Shevek says of Tirin that ‘he was extremely vulnerable’ and that ‘an artist can’t hide behind the Truth. He can’t hide anywhere.’ Which makes it harder for artists to defend their choices.

The text then goes on to describe another relevant aspect of cancel culture: the fact that it instils a climate of fear. Artists then worry before creating, and they self-censor. ‘We fear being outcast, being called lazy, dysfunctional, egoising. We fear our neighbour’s opinion more than we respect our own freedom of choice.’ Shevek argues that our behaviour becomes controlled by what we think others are going to think of us, that we limit ourselves out of ‘convention, moralism, fear of social ostracism, fear of being different, fear of being free.’

That’s probably the most damaging aspect of cancel culture, in my eyes: it frightens artists – even and sometimes especially artists from minority communities, who most need to be nurtured – and it discourages them from creating art.

Criticism VS Cancellation: What we might gain

Shevek describes the process thus: ‘We’ve made laws, laws of conventional behaviour, built walls all around ourselves, and we can’t see them, because they’re part of our thinking.’

Now, arguably, some walls are needed. For society to function, we do need some conventions that we all agree upon and enforce. As to whether we should censor people at all, it’s worth noting that freedom of speech has always been limited in democracies (libel and defamation are accepted limitations to freedom of speech, for example). So we do build walls. The question is, which walls are legitimate?

If an artist has committed a crime and, as a reader, I don’t want to support them financially by buying their art, I think a boycott is legitimate. It doesn’t mean the art isn’t interesting and enriching. It just means that, if justice isn’t being served, then I do agree that boycotting the artist financially might be a solution. However, how about situations like Tirin’s, where it’s about the art, not the artist? Do certain worldviews need to be opposed? Well, yes. We can only have good, useful and healthy beliefs if we distinguish them from bad, destructive and toxic beliefs. But these beliefs will change according to our class, culture, lived experience, etc. They will rarely be agreed upon by everyone. There is also a difference between criticising something and boycotting it, between questioning a piece of work and asking for it to never see the light of day.

Criticism doesn’t require cancellation (quite the opposite, it requires reading/sharing the work). And controversy isn’t always a successful way of punishing an artist, if that’s the goal: sometimes controversy is akin to popularity, especially in our very polarised world. It doesn’t mean we’re having a healthy conversation; it can simply serve to clinch opposing camps. And sell books, of course, which is good for the economy, but not particularly great for the author or the readers.

I also think we should be wary of the difference between artists who defend a different worldview from ours explicitly, as their public persona, (but it’s not necessarily present in their art); or art that we feel perpetuates harmful tropes or goes against our worldview (independently from the artist). We can deal with art that goes against our worldviews by refusing to engage with it, or criticising the aspects we don’t like (without harassing the artist, I’d like to stress). It gives the artist a chance to surprise us by creating something we like later on in their career.

If an artist has a public persona, then the problem has shifted slightly. If they’ve got a big enough following, or sell enough books, then they have economic power. Online, they may have power akin to an influencer’s: the power to be heard, quickly and easily, by a lot of people. The power to sell ads. The problem shifts to how we manage people with soft power in a society where people’s attention is used as currency. That is outside of the scope of this article, I think.

Conclusion: What’s the alternative?

If not the audience, I’m not sure who gets to decide which artists get heard – the lawmaker, the state, the gatekeepers? Instinctively, I assume it’s better if the collective decides. In that case, should we accept cancel culture as a democratic process akin to boycott? Or is ruling through convention and group wisdom – as the people do on Anarres – the wrong way of going about it?

One could argue that cancel culture is a semi-democratic process, in that it’s not censorship from the top down, but from the bottom up. In all cultural industries, there is a form of gatekeeping, where some works are chosen to be put forward and others are not. So it’s not so much that we can’t make decisions about what we want to read or not, who we want to see published or not – as a society, we already do this – but who gets to decide.

But then, cancel culture is rarely democratic. I’ve been using the term ‘the audience’ but, as Shevek points out:

But who are these people you keep talking about – ‘they’? ‘They’ drove him crazy, and so on. Are you trying to say the whole social system is evil, that in fact, ‘they’, Tirin’s persecutors, your enemies, ‘they’ are us – the social organism?

Internet isn’t the social organism. For one thing, we’re not represented fairly. On the internet, everyone doesn’t have an equal voice: people with large social media followings have ‘louder’ voices, and are thus more powerful. It’s a collective, yes, but one of unequal influence and power. And not everybody concerned by a debate engages with it, either. Vocal parts of the internet are not representative of all readers.

At the end of this article, I find that I have more questions than answers. What’s the alternative? In theory, authors are free to create what they want. In reality, they’ll be subject to gatekeepers in the publishing industry, fear of cancel culture, economic pressure, etc. Should this affect what we write? If not, what can we do to change those factors? Would it be better if there were no industry gatekeepers, but the audience got to decide what got published? Should nobody decide? In that case, what do we do about racist, misogynistic, homophobic, hateful content? Is it enough to simply write hopeful, kind, beautiful pieces and hope that, through the art, we’ll oppose that worldview, without needing to cancel the artist directly?

I’m tempted by that solution. I don’t want to be the sort of person who picks fights with other artists. But I do want to be the person who writes the counter-narrative.

I don’t have the final answers. And neither, most probably, does Le Guin. But her character Shevek does find an answer that works for him: ‘Those who build walls are their own prisoners. I’m going to fulfil my proper function in the social organism.

I’m going to go and unbuild walls.’

As a closing note, I’d like to thank Mark Tunick for his thought-provoking piece: The Need for Walls: Privacy, Community and Freedom in the Dispossessed, and the PhilPapers website for their open access to philosophical archives. Here’s the original article for those who want to do some further reading: https://philpapers.org/archive/BURTNU.pdf

What’s happening with me – Snow on Snow

I’m convinced there’s a Christmas carol with the lyrics ‘snow is falling, snow on snow, snow on snow on snow’ but I cannot seem to find it and also, annoyingly, can’t remember the tune. So I’ve been not-humming this as I walk about Clermont-Ferrand. We’ve had two good snowfalls, which stuck around long enough to throw snowballs to Sancho and stop all the buses from driving uphill for a day.

Christmas has been very intense for me this year, with family health issues adding up on top of picking which country to celebrate in – the usual issue with families split between countries. I’ve also been looking for a job and may have found one, which means I’ll be much busier in the months to come. Still, it’s nice to be back home for a while. I’ve also been keeping a friend’s dog, which means I’ve had a chance to dual-wield snowballs: if I don’t throw one to both dogs at the same time they get jealous. They both jump in synch to catch it – Sancho, as a border collie, is very focused on actually catching the ball; his friend, an Australian shepherd, jumps in the air for the fun of it, and only rarely catches anything.

Alas, I cannot have a snowball in each hand and a camera, so you will have to take my word for it that they are one of the cutest sights to behold!